“Save yourself” (Lk 23:37) was the contempt hurled at Jesus as he hung upon the cross. The religious leaders, the Roman guards, even one of the criminals hanging with him, could see nothing but death in the crucifixion of Jesus. Even Jesus, the night before he died, experienced the temptation that he had been completely abandoned by his closest friends and by his Father. However, he also remembered at the Last Supper God’s presence throughout his life and throughout the history of Israel. With his disciples, he sang Psalm 136, which has the refrain, “for his mercy endures forever.” Thus, Jesus was able to embrace the cross as an act of trust in his Father’s fidelity and as an act of love for humanity; by his death he would destroy death and open eternal life for all.

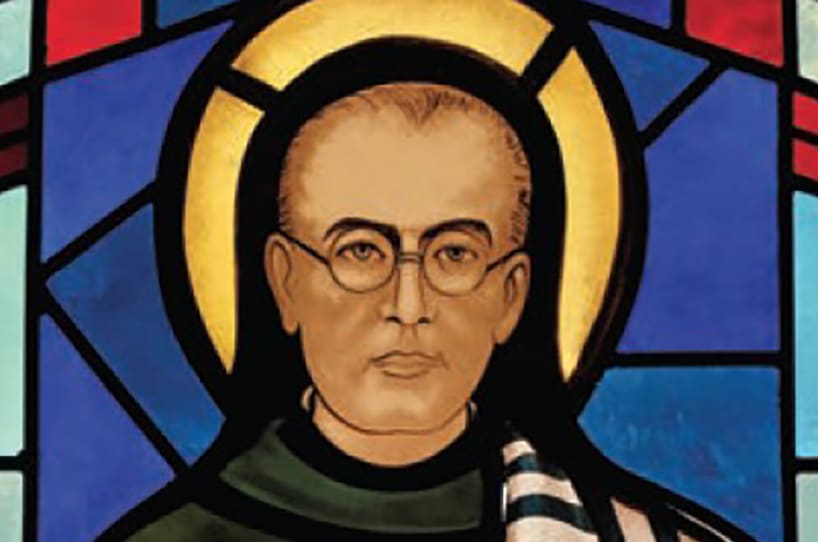

Is it possible to live by the same confidence Jesus had? We do not need to guess at an answer, because we have an example of a person who did: St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe.

Brother to all mankind

He was christened Raymond Kolbe shortly after his birth in Poland on Jan. 9, 1894. His parents, Julius Kolbe and Maria Dabrowska, were devout people who loved God and country. Julius, an ethnic German, would later be arrested as a member of Jozef Pilsudski’s Polish Legions who were fighting for Polish independence from Russia. Later still, when Maximilian had grown, both parents entered religious life. Maximilian followed the same route, first by flirting with the desire to fight for Poland like his father and then by pursuing what would eventually become his life’s vocation, the priesthood. It seems it was a broadening of his capacity to love not only his Polish brothers and sisters but also all mankind.

After his ordination on April 29, 1918, Maximilian was like an exploding star sending light into the dark areas of his place and time. He worked tirelessly over the next 20 years for the conversion of sinners, to preach the Gospel of Christ so that everyone might share in the love of God. His model of discipleship was Mary, the virgin Mother. With her as his guide, Maximilian worked indefatigably promoting faith, hope and love in God. He founded the Crusade of Mary Immaculate that had cells throughout Poland — men and women praying with Mary for the world and imitating her example of joyful obedience to God’s will. He also published a journal called the “Knight of the Immaculate,” which had as its mission to illuminate the truth and show the true way to happiness. By 1927, 70,000 copies were circulating in the country. The crown jewel to all his pastoral activity was the founding of the friary named Niepokalanow (City of the Immaculate), from which he would send priests to the missions.

His ministry in Poland was immensely generous, and yet Maximilian remembered the words of Jesus to his disciples, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Mt 28:19-20). Supported by these words and promise of Jesus, Maximilian set out for the Far East in 1930. He would travel to China, Japan and India over the following six years until ill health would force him to return to Poland in 1936. He founded a couple of monasteries along the way, including one in Nagasaki that remains a center for Japanese Catholics.

Missionary of mercy

Ill health may have curtailed his travels, but it failed to reduce his efforts at evangelization through preaching and writing, and then in 1938 through something new: a radio station. Nevertheless a greater activity awaited him, one that would conform him to his Savior, and it was brought on by the invasion of Poland by Nazi troops in September 1939.

Since Maximilian and his fellow friars operated a center of evangelization, they were special targets for the Nazis. Maximilian was arrested on Sept. 19, 1939.

When it became known that he had German ancestry, he was offered an opportunity to sign the Deutsche Volksliste (German People’s List), which would have given him the rights of a German citizen. Maximilian, however, had long ago embraced his common ancestry with all mankind, and he refused to accept an advantage so xenophobic in its intentions. The Nazis released him from prison on Dec. 8, 1939, but kept him and his community under close watch.

Back at Niepokalanow, despite the danger he was in, Maximilian got back to work. He set up a hospital in the friary and made room for 3,000 refugees, 2,000 of whom were Jewish. Everything was put at the service of these people who had been displaced from their homes. Maximilian also used his publishing machinery and radio broadcasts to condemn the Nazi aggression. In January 1941, in the last edition of the “Knight of the Immaculate” that he was able to print, Maximilian gave his readers the antidote to the Nazi scourge: “No one in the world can change Truth. What we can do and should do is to seek truth and to serve it when we have found it. The real conflict is the inner conflict. Beyond armies of occupation and the hecatombs (the sacrifice or slaughter of many victims) of extermination camps, there are two irreconcilable enemies in the depth of every soul: good and evil, sin and love. And what use are the victories on the battlefield if we ourselves are defeated in our innermost personal selves?”

Conformed to Christ

Among the readership that January, of course, were the Nazis themselves, and they understood the power of Maximilian’s witness. They arrested him, along with four other Franciscans, on Feb. 17, 1941. Maximilian was transported to Auschwitz, where he donned the striped prisoner uniform with identification number 16670 stitched across the chest. Since he was a priest, the guards singled him out for severe beatings. Eyewitnesses reported after the war that Maximilian suffered the abuse quietly. They also recounted that Maximilian continued his ministry in the camp clandestinely: celebrating Mass, hearing confessions and consoling others with words of hope. When food rations were doled out, Maximilian took the last place in line in order that others could eat.

Maximilian’s entire ministry was focused on serving others, and thereby he imitated Jesus, whose own ministry was described by Pope Francis in Misericordiae Vultus (“The Face of Mercy”) in this way: “Jesus, seeing the crowds of people who followed him, realized that they were tired and exhausted, lost and without a guide, and he felt deep compassion for them. On the basis of this compassionate love he healed the sick who were presented to him, and with just a few loaves of bread and fish he satisfied the enormous crowd. What moved Jesus in all of these situations was nothing other than mercy, with which he read the hearts of those he encountered and responded to their deepest need” (No. 8).

In Auschwitz, Maximilian understood that the deepest need of his fellow prisoners was to see that hope and love were still real, that the hatred and inhumanity of the Nazis could not stifle authentic love. His own experience of God’s love moved him to share it with everyone in the camp, even the guards who mistreated him. When the S.S. camp leader announced that 10 men would be executed in retribution for the disappearance of a prisoner, and when one of the 10 chosen cried out in desperation at the thought of never seeing his family again, Maximilian acted on his deepest beliefs: He offered his life in place of the desperate prisoner. Why? Because Jesus had taken Maximilian’s place, and everyone’s, when we were sentenced to death for our sins. By his wounds we have been healed (1 Pt 2:24). Jesus destroyed the power of death and opened the way to eternal life. Maximilian knew this, but he wanted everyone in the camp to know it, too.

David Werning writes from Virginia.