This is the first in a yearlong series that looks at the Church’s 12 most recent popes and the marks they’ve left on the Church. The series was published in the first issue of each month throughout 2018.

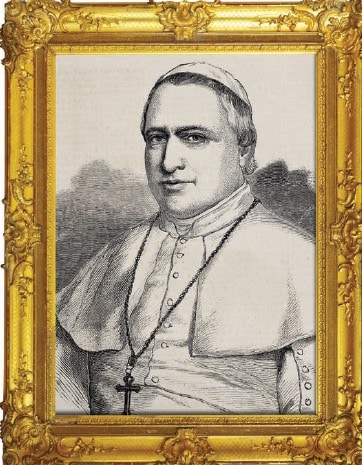

The pontificate of Blessed Pius IX was in some ways a study in contrasts. Starting as a liberal reformer, Pope Pius ended as a determined conservative. Despised by the secular establishment of his day, he was revered by Catholics around the world. Defeated in his efforts to retain the temporal power of the papacy, he greatly expanded its spiritual and moral authority.

But there is a fundamental unity here allowing a chronicler of the popes to sum up this self-styled “Prisoner of the Vatican” as the one who more than anybody “effectively created the modern papacy.” Not coincidentally, perhaps, he also served as successor of Peter longer than anyone in history so far — well over 31 years, between 1846 and 1878.

Turbulent transition

Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti was born in northern Italy on May 13, 1792, the fourth son of a count. As a youth he suffered from what appear to have been epileptic seizures from which he was cured. After studies in Viterbo and Rome, he was ordained a priest in 1819 and held various posts in the service of the pope, including serving with a papal mission to Chile in 1823-25.

He headed the sees of Spoleto (1827-32) and Imola (1832-40), and was named a cardinal in 1840. He was elected to succeed the ultra-conservative Pope Gregory XVI at the conclave of June 1846. At the time, he was regarded as a moderate liberal and known to be an Italian patriot.

The new pope — “Pio Nono” to everyone — set about living up to his reputation, introducing into the Papal States, that swath of central Italy ruled for centuries by the popes, reforms like railway service, gas street lights in Rome and abolishing the requirement that Jews attend weekly Christian sermons.

But Pius IX made it clear that he had no intention of giving up the Papal States, which he and others considered essential to the independence of the papacy. This soon brought him into conflict with an Italian nationalist movement under largely anticlerical control.

| Blessed Pius IX at a glance |

|---|

|

Born Giovanni Maria Mastai-Ferretti, May 13, 1792 Ordained a priest in 1819, a bishop in 1827 and made a cardinal in 1840 Pope from June 16, 1846-Feb. 7, 1878 Reigned during the loss of the Papal States Infallibly defined the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, Dec. 8, 1854Oversaw the First Vatican Council, 1869-70, which declared papal infallibility First pope to be photographed Beatified Sept. 3, 2000 |

In November 1848 — a year of revolutions throughout Europe — the lay prime minister of the Papal States was assassinated, an armed rebellion broke out in Rome, and the pope fled to Gaeta in Neapolitan territory. He was restored by French troops and returned to Rome in 1850. For the next 20 years, his reign was backed by a French and Austrian military presence, while the nationalist forces seized much of the Papal States, leaving the pope with only a small strip along the coast and the city of Rome itself.

It was in these years of political defeat for Pius that ultramontanism grew and spread in the Church. This was the view of the Church that, looking “beyond the mountains” to Rome, focused Catholic identity and loyalty increasingly on the see of Peter and the person of the pope. It also was a time for the flowering of devotions, including especially devotion to the Virgin Mary. Aiding and abetting this upsurge of Marian devotion was Pius IX’s action on Dec. 8, 1854, infallibly defining the dogma of the Blessed Virgin’s Immaculate Conception — that Mary, in the words of the decree, “at the first instant of her conception … was preserved immune from all stain of original sin.”

Reeling against modernity

Two other things stand out as key events of the pontificate during these years: the Syllabus of Errors and the definitions of papal infallibility and papal primacy by the First Vatican Council.

The syllabus (or list) was attached to an encyclical entitled Quanta Cura, dated Dec. 8, 1864, the feast of the Immaculate Conception, in which Pope Pius strongly condemned various errors of the day, including naturalism and socialism. “Where religion has been removed from civil society and the doctrine and authority of divine revelation repudiated,” he declared, “the genuine notion of justice and human right is darkened and lost, and … brute force is substituted.”

The Syllabus of Errors then proceeded to set out 80 propositions which Pius IX had declared to be erroneous, including atheism, pantheism, rationalism, indifferentism (the view that one religion is as good as another), socialism, communism, secret society and the idea that the secular nation-state has authority over the Church. Accompanying the list and providing the necessary context for understanding it were citations to the previous papal documents in which these errors were condemned.

The passing of time has shown the pope to be right about many of these matters. When, for example, Pius IX condemns the proposition that “in a conflict between the laws of the two powers [church and state], the civil law prevails,” he could almost be speaking of the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century.

But critics of that day would hear none of that. The secularist French government tried to keep the papal document out of the country and told priests not to preach on it. William Ewart Gladstone, head of the British Liberal Party and a future four-time prime minister, wrote that the practical effect of the syllabus was that no one could be a Catholic “without renouncing his moral and mental freedom.”

This brought a sharply worded response from Father — later Cardinal — John Henry Newman, a scholarly convert who argued that it was missing the point not to read the pope’s words in context. Especially this was true of proposition 80, which rejects the idea that “the Roman pontiff can and should reconcile himself to progress, liberalism and the modern culture.”

This was drawn, Father Newman pointed out, from a papal statement three years earlier saying those claiming to represent “progress, liberalism and the new civilization” often used these as vehicles for attacking the Church. In England, he noted, “it is the common cry that liberalism is and will be the pope’s destruction; and [those who say that] wish and mean it to be so.”

First Vatican Council

The ecumenical council of 1869-70 continued and intensified Pope Pius IX’s defense of the Faith and the papacy on two key matters of doctrine — papal infallibility and papal primacy: the popes’ authority to teach and govern the Church.

Although a minority of bishops questioned the timing, the result on infallibility was a formulation that in the end won overwhelming approval, 533-2. The teaching of the pope was declared to be infallible when exercised in defining a doctrine of faith or morals to be held by the whole Church.

On primacy, the council declared the jurisdiction of the pope to be preeminent, “ordinary,” “episcopal” and “immediate,” requiring “true obedience” on the part of all members of the Church and extending not only to faith and morals but “matters that pertain to the discipline and government of the Church throughout the whole world.”

Vatican I had more work in mind, but it did not get to do it. The French garrison in Rome was withdrawn in 1870 to fight in the Franco-Prussian War, leaving Rome open to the forces of Italian nationalism. The bishops promptly went home, the nationalists moved in, and the pope withdrew into the Vatican enclave, declaring himself “the Prisoner of the Vatican.” And a full treatment of the theology of the Church and the role of bishops would have to wait more than 90 years, until the Second Vatican Council and its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium (1964).

Meanwhile, although “prisoner” he may now have been, Pius IX’s popularity nevertheless soared, abetted by technological innovations that carried the words and images of the pope to Catholics around the world, while also carrying a growing number of pilgrims to Rome to see and pray with him in person. By the time of his death on Feb. 7, 1878, this helped make him what historian Eamon Duffy calls “a popular icon.”

But so, above all, did the goodness and charm of the man himself. Even his critics, Duffy writes, “admitted that it was impossible to dislike him.”

“He was genial, unpretentious, wreathed in clouds of snuff, always laughing. His sense of the absurd sometimes got the better of him, as when some earnest Anglican clergymen begged his blessing, and he teasingly pronounced over them the prayer for the blessing of incense, ‘May you be blessed by him in whose honor you are to be burned.'”

People aren’t beatified for having a sense of humor, but with Pius IX it surely didn’t hurt. Pope St. John Paul II declared him a Blessed — one step away from Catholic sainthood — on Sept. 3, 2000.