Many of us have had the experience: We were the leading candidate for a more senior position in our organization. We were encouraged by many colleagues. We put ourselves out there and made our case for the promotion, only to have it announced that a less-experienced outsider had been named to the position instead.

We were humiliated, professionally and personally, and before the eyes of our colleagues, friends and family.

Grand jury reports, the malfeasance of people we trusted, or the bad example of leaders — all of these humiliate us as practicing, or even somewhat-practicing, Catholics.

Humiliations can be personal or communal. Strong emotions — anger, shame, disappointment — accompany our humiliations. And our humiliations bring both pitfalls and opportunities.

Urges to flee, cast blame

My initial reaction to humiliation is to leave it behind me as quickly as possible. How far can I distance myself from the favoritism, or the reports, malfeasance and bad example?

The urge to “put it behind me” can be almost overwhelming. Yet personal responsibility to family or others can make quitting impossible. The abuse crisis, for instance, will go on for years in the form of state-level investigations and revelations. Avoiding immediate or long-term engagement with humiliations may not be possible for Catholics.

Humiliations call me to patiently work through them rather than run away. The problem with running away is that humiliations catch up with us. The emotional experience can be rooted deep in our minds and surface the next time we consider a promotion or enter a church, and they might influence our behavior in negative ways.

The urge to blame someone else is another pitfall. Why can’t the professionals in human resources prevent unfairness? If we had better leadership in the Church, or if we quarantined all homosexual Catholics, wouldn’t the crisis be resolved? These forms of facile “wishful thinking” distance us from the humiliation but leave it unresolved.

The opportunity is to grow in the virtue of humility. Rather than trying to get it all over quickly or blame it on someone else, perhaps we should embrace the “abjection” in our humiliations. St. Francis de Sales wrote in “Introduction to the Devout Life” (Part 3, Chapter 6), “… besides the hurt, we incur shame; we must love this abjection.”

The virtue of humility

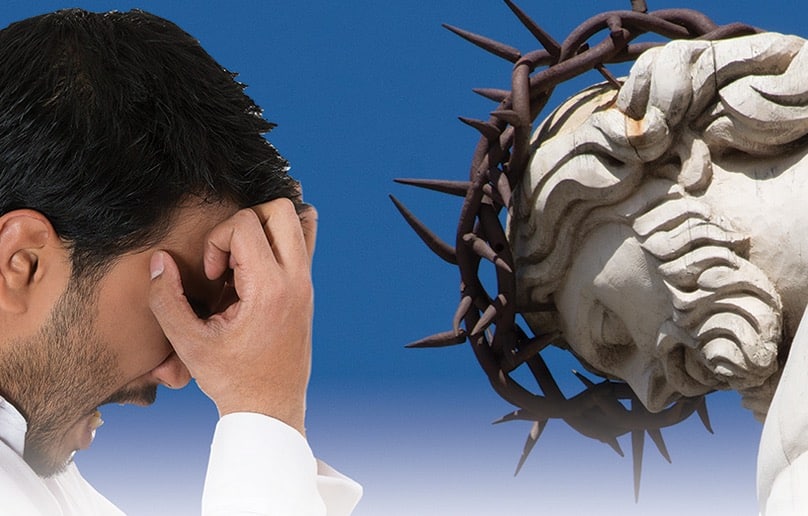

Humility is a foundational virtue for spiritual growth. Jesus humbled himself for our salvation, accepting even death on a cross. St. Paul summarizes Jesus’ humility in Chapter 2 of Philippians. For followers of Jesus, humility is a necessity.

We live in a culture where success, achievement, upward mobility and wealth are lionized. In the political town I live in, it is clear that “success has many parents, but failure is an orphan.” The “downward mobility” of a Savior who humbled himself and seemed like a failure is admired, even pondered, but only occasionally imitated. Pride easily surpasses humility.

| Residual Church Pride |

|---|

Years ago, when I was growing up in Philadelphia, I learned that Catholics had the true Faith, but I also got the impression that the Church never made a serious mistake!

As an altar boy, I saw that we made numerous practical mistakes. Subsequently I learned enough theology and Church history to nuance considerably what I had learned about Church teaching. In my two decades of ecumenical dialogue, I became aware of a certain residual pride in our Church. We were the biggest, believed we had a lot of answers and sometimes thought ourselves a little better than our Protestant friends. Part of this residual pride was related to the post-World War II arrival of Catholics in the mainstream of American life (e.g. the election of President John F. Kennedy). Another part was the residue of our years of strife and competition with Protestant America, which ended officially with the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). In the last two decades, the ongoing humiliations of the abuse crisis has forced us to acknowledge our sinfulness and limitations. As a Church, we can also be blind in our own concerns. Some of our blindspots as a community are very visible right now. I feel sure that others will come to the fore later. As individuals and as a community, we will always need to know ourselves better and come to love our abjection. Paradoxically, this abjection, if we can love it, will be a profound source of spiritual growth. A deeper conversion to Christ who humbled himself for us is exactly what we need. If we come closer to Christ, we will also come closer to other Christians and, rather than being prideful, will be open to receiving their spiritual gifts as well. Pride will give way to realism and to God’s will. |

Humility requires me to look clearly at the reasons behind my being a person of Christian faith. How much does my faith involve my need for certainty, for consolation and for relief from anxiety? How much does my faith involve friendship with Jesus and living out his message of love and service to others?

Sometimes we shape our faith to meet our human needs. At other times we get to know the Jesus of the Gospels and try to live out his challenging message.

Accepting our humiliations, acknowledging embarrassment and shame, and then seeking to live humbly, is difficult in both our personal and communal lives. Personal humility involves seeing ourselves as we truly are, acknowledging both the gifts God has given us and our faults, sins and disabilities. St. Francis de Sales said that “the true virtue of humility is the real knowledge and voluntary recognition of our abjection.”

Saint Francis de Sales teaches first about outward humility. To receive the grace of God, we need to empty our hearts of our own glory, of our pride and our need for regular recognition. “Honor received as a gift is excellent but becomes mean when exacted, sought after and demanded,” he writes.

Interior humility goes deeper. It does not make a show of itself. Rather the truly humble person is grateful for the many blessings received from God. He or she comes slowly to realize that all we have is a gift.

External and internal humility go together. “Let us never lower our eyes without humbling our hearts. Let us not make a show of wanting to be the last unless we really wish it,” he admonished.

The highest point of humility involves loving our abjection. Can we come to love our humiliations?

Finding patience

In de Sales’ spirituality, the virtue of humility is closely linked to patience. “The really patient servant of God bears with equanimity the humiliating trials as well as the honorable,” he writes. Like all the “little virtues” de Sales recommends, patience is best practiced daily. Ordinary life provides ample opportunities to learn to be patient with ourselves and with others. My favorites are trying to be patient while: 1) driving in the Washington traffic; 2) participating in meetings; and 3) waiting for God’s plan to become clear.

My experience is that loving my abjection is a sometime thing. My need to get it over with is great; my patience is limited. I find it helpful to share humiliations with a spiritual director or spiritual friend. This releases some of the emotion connected to the humiliation, making it a little more manageable.

Having de-escalated a bit, I begin to ask myself “What can I do to help make the situation a little better?” Perhaps a call or email to human resources would be more constructive than just blaming. Perhaps I can help in the healing process for not just victims, but all in the Church who are affected.

Entering a healing process for others involves acknowledging my own need for healing from unresolved past hurts and sins. Years ago, the spiritual writer Father Henri Nouwen pointed out that all of us are wounded healers.

Paradoxically learning to deal with our humiliations, with our own woundedness, can be key to becoming a healing presence for others.

Humiliations help us embrace the paschal mystery.