In his last command before the Ascension, Christ commanded the apostles to make disciples of all nations.

Through the centuries, Christian missionaries have taken the Great Commission seriously, traveling to various nations and continents to spread the Gospel, oftentimes becoming martyrs for their fidelity.

“Mission work is vital. In fact, I think you can easily make the case based on the Gospels, Church history and the Magisterium that (mission work) is the essential function of the Church, and it’s as important now as it’s ever been,” said Matthew Spizale, communications director for Family Missions Company, a private association of the faithful based in Louisiana that sends Catholic families and singles to be missionaries for the poor around the world.

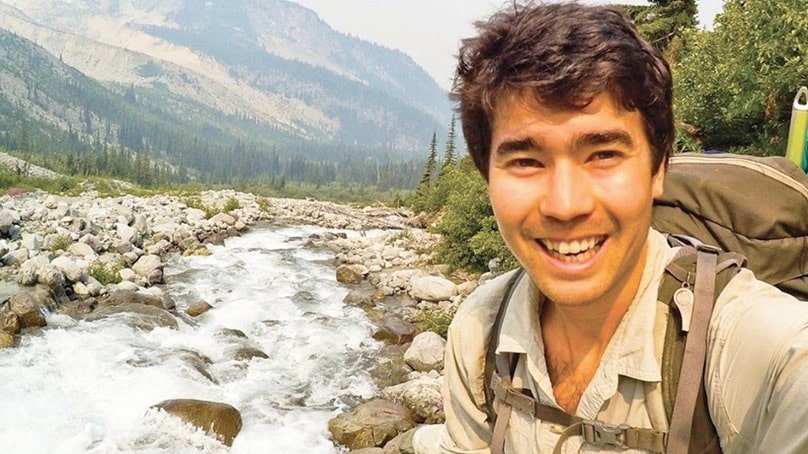

The nature of mission work has been a recent topic of discussion within Christian circles in the wake of the highly publicized death of John Chau, a 26-year-old American who was killed on Nov. 17 while trying to contact a remote tribe on North Sentinel Island in the Indian Ocean.

Mixed reactions

To some observers, Chau, an evangelical Christian, was naive, reckless and somewhat arrogant. To others, he died a martyr trying to spread the Good News to a remote island in the Indian Ocean.

“I don’t know: a kid wading ashore, unarmed, wearing only a pair of shorts, and carrying only a Bible? Say what you want about his prudence. I will speak of him with honor,” Bishop Robert Barron, auxiliary bishop of Los Angeles and founder of the Word on Fire Catholic media ministry, said in a Dec. 4 blog.

According to reports, Chau paid a group of local fishermen to take him to the island, which the Indian government has placed off-limits because of the tribe’s hostility to outsiders, as well as the possibility that they may lack the immunity needed to fight modern diseases.

None of that deterred Chau, a self-styled explorer and missionary who had long been interested in the North Sentinelese people. He dreamed about bringing the Gospel to them and kept a journal where he detailed his interactions with the tribe before his fatal trip.

“I hollered, ‘My name is John, I love you and Jesus loves you,'” Chau wrote of one earlier encounter, according to the Washington Post, which also reported that Chau recounted trying to speak the tribe’s language and singing worship songs, which elicited angry reactions.

In another penciled journal entry, Chau reportedly wondered if the island was “Satan’s last stronghold” where none had ever had the chance to hear the Lord’s name.

To a few observers, including some experienced Catholic missionaries, that line about piercing “Satan’s last stronghold” shows that Chau, though sincere, may have lacked prudence and possibly had somewhat of a Messiah complex.

“To my Catholic ear, that’s a horrible thing to hear. How would you know (North Sentinel Island) was Satan’s last grip on Earth? What do you base that kind of judgement on?” said Donald R. McCrabb, the executive director of the United States Catholic Mission Association, an organization that supports U.S.-based home and international missionary groups.

To the nations

McCrabb told Our Sunday Visitor that Chau had “a very antiquated approach” to mission work that seemed modeled on how European missionaries evangelized while accompanying seafarers during the Age of Exploration in the 15th and 16th centuries.

“We just don’t do mission that way any longer,” said McCrabb, who contrasted Chau’s approach with that of Sister Dorothy Stang, a Notre Dame de Namur sister who was asked by Church leaders in Brazil to serve the indigenous population in that country. Sister Dorothy was killed in 2005 for her work in fighting for the property and land rights of rural workers and peasants.

“The land owners and barons didn’t like that, and that’s what resulted in her death,” McCrabb said.

Unlike the Notre Dame sisters, Chau had not been invited to North Sentinel Island, even as he clearly knew the risks he was taking. In his journal, Chau wrote about not wanting to die, reflecting the night before he was killed if he was seeing the sunset for the last time.

“It’s almost like a modern-day version of the movie, ‘The Mission,'” McCrabb said, referring to the 1986 film about Spanish Jesuit missionaries in the 18th century who evangelized a South American tribe. The film shows a missionary priest tied to a cross and sent over a waterfall after the tribe had killed him.

In his blog, Bishop Barron also drew on the parallels between Chau’s story and “The Mission.”

“Fired by Christ’s call to bring the Gospel even to the ends of the world, Chau resolved to venture to this dangerous and primitive place,” wrote Bishop Barron, who added that Christianity is a missionary religion and that Christians across the centuries have been willing “to risk everything in order to bring the Gospel of Christ to those who do not know it.”

“I realize that even the most sympathetic of observers might well be tempted to see this simply as a waste of a life, a debacle born of naïveté and foolish zeal,” Bishop Barron wrote. “And yet … Jesus did indeed instruct his disciples to bring the Gospel to every nation — it was in fact his final command.”

Nature of mission

The commentary has been less charitable in the secular media, where writers have attacked Chau for disregarding the laws against contacting the tribe and possibly exposing those people to diseases. The very nature of mission work was also called into question, with some dismissing it as a relic of Western imperialism.

Spizale, from Family Missions Company, said missionaries often feel a tension between the Lord’s charge to make disciples of all nations while navigating complex realities on the ground that often include volatile political, legal and cultural circumstances.

“That’s a tension we hear in the way people are writing and talking about this most recent incident,” Spizale said. “Even in Christian circles, people are wondering what they would do there, and I can’t say that I precisely know the answer either.”

Father Chris Saenz, a Columban Fathers missionary priest who recently returned home to the United States after 17 years in Chile, told OSV that the Mapuche indigenous community in that country was often not happy to see him and other missionaries, but he added that those tensions eased over time with dialogue.

“You have to get to know the people first,” Father Saenz said. “The people in that area weren’t wild about our presence, but oftentimes we would go to their houses and visit. We’d sit down, have a coffee and talk about anything other than religion. We just met on a basic human level.”

Father Saenz said he could relate to the zeal and romanticism that Chau displayed for mission work.

“I had a bit of that too when I was a young man,” said Father Saenz, 51, who added that an experienced missionary would know other ways to engage a remote community, such as working through backchannels and developing relationships over time by learning the people’s language and culture.

“As a missionary, you can create bridges,” Father Saenz said. “You can narrow the gaps between peoples.”

Brian Fraga is an Our Sunday Visitor contributing editor.