For the Christian, sentimentality is a temptation. The sentimental person is so driven by the desire for strong affections, reducing nearly everything to kitsch or a nostalgia for some imagined past.

This sentimentality can easily seep into the feasts of the Christmas season. We imagine the infant Christ, surrounded by his parents, the friendly beasts, the three Magi and the shepherds. Perhaps there’s a bit of snow on the ground in our imaginations. We delight in this image, longing to return to a simpler time when Christ was born and the world was at peace.

Christmas is decidedly the feast of peace. In the Word made flesh, Jesus Christ, we contemplate the union of humanity and divinity. We see the possibility that each of us, if we imitate the self-giving love of the babe in the manger, can become like God.

But Christmas is the feast of peace precisely because the world needs peace. It needs a peace that it cannot give itself. And that’s where sentimentality leads us astray.

| Epiphany of the Lord: Jan. 6, 2019 |

|---|

|

IS 60:1-6

PS 72:1-2, 7-8, 10-11, 12-13 EPH 3:2-3A, 5-6 MT 2:1-12 |

The advent of the Magi, coming to adore the newborn savior of the world, takes place in the context of violence.

The Magi come to Herod, asking about the newborn king. Herod is a puppet king. Rome has allowed him to take on the trappings of kingship, but he is no David. He is no Solomon.

For this reason, the query of the Magi elicits a crisis in Herod. If there is a rival power to his own, someone who could wrestle away control, he has to be found out.

Herod sends the Magi on a diabolical mission, unbeknownst to them. He says that he will come to adore this newborn king.

He has no intention of doing so. Herod plans to snuff out this power, to rip apart the Word made flesh. When the Magi depart by another way, having been warned in a dream, Herod grows angry and responds with violence: “He ordered the massacre of all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity two years old and under … ” (Mt 2:16).

This violent act on the part of Herod reveals precisely how unsentimental Christmas is. The birth of Christ is the appearance in the world of total, absolute, divine love.

Jesus in his very person brings about peace between God and man. The “daybreak from on high” (Lk 1:78) — born in the middle of the night at the darkest hour — shines forth the light of divine love.

But not everyone greets the appearance of this love with a song of praise. The gifts of the Magi show this to be true.

Gold for a king. Frankincense for a priest. Myrrh for a corpse. Myrrh, used to anoint a body for burial, is given to an infant. Christmas is not a sentimental feast.

But, it is a joyful one. God reveals to us in the coming of the infant, in the adoration of the Magi, that the time of salvation is at hand.

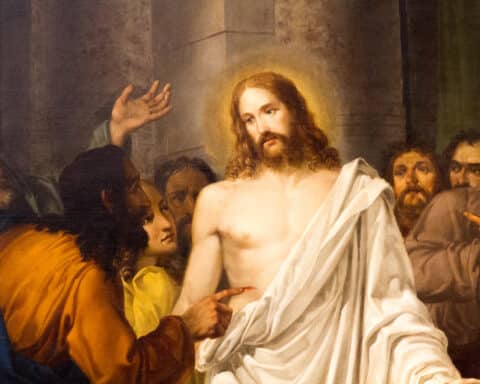

The Word became flesh. The Word became infant, the speechless one. And eventually, the enfleshed Word will take upon himself the sins of the world, revealing that silent love will defeat sin and death: “Though harshly treated, he submitted and did not open his mouth; Like a lamb led to slaughter or a sheep silent before shearers, he did not open his mouth” (Is 53:7).

The feast of the Epiphany reveals to us that the powerless one, the babe, is the Savior of the world. For that reason, it reminds us that we live in a world that needs saving.