The greatness of a piece of art can be measured in various ways: its historical impact, the degree to which it moves the viewer, the skill of its technical execution. But the fact remains that the subject matter is often the key. The most beautiful art depicts the most beautiful subject matter. The excellence of the subject influences the excellence of the piece.

It is not surprising, then, that Mary, the Mother of God, remains one of the most common and moving subjects in the history of art. Although we hear very little about her in the Gospels, her life has been imagined by countless artists throughout the centuries. Alongside Christ, she forms one of the key figures in the Western artistic tradition.

Having been formally proclaimed the Mother of God in 431 at the Council of Ephesus, we find depictions of her throughout the centuries in various media: painting, sculpture, mosaic. Marian images became especially common in liturgical and devotional art after the Edict of Milan in 313, which allowed Christianity to exist openly within the Roman Empire.

She is not only the Mother of God. Hanging on the cross, Jesus also gave her to us to be our mother (cf. Jn 19:26-27). Christians throughout the ages have found much solace in their prayers to her and in the visual depictions that remind us of what humanity is to receive through the transformative action of grace. Here, we take a tour through a small selection of images which tell of the story of Mary’s life and the ways in which she is constantly trying to bring us closer to her son.

“The Annunciation”

Jan van Eyck, c. 1434-36, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

We first hear of Mary directly in the Scriptures as the Archangel Gabriel appears to her, announcing her role in salvation history (cf. Lk 1:26-38). In Van Eyck’s depiction of the Annunciation, we see the encounter in which Gabriel addresses her with the words, “Hail, one who is full of grace!” Mary in turn replies, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” With this exchange, her free participation in God’s plan of salvation for the world unfolds. From above, we see the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove contained within rays of light descending upon Mary. Through the power of the Spirit, the Word — Jesus Christ — is to become incarnate in the flesh. Gabriel, who is carrying God’s message, is dressed in regal vestments that show us the majesty of the one from whom the message is coming. Mary, for her part, is shown with a belt around her flowing gown, a manner of dress typical of a woman carrying a child. Both figures are standing upon a floor decorated with scenes from the Old Testament and the signs of the zodiac that remind us that the people of Israel and the whole of creation has pointed to this pivotal moment in history.

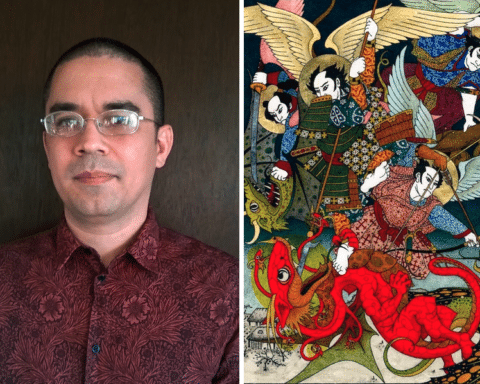

“The Adoration of the Magi”

Edward Burne-Jones, 1904, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Surely, one of the most joyful moments in Mary’s life was the birth of her son. Not only did she witness her humanity inextricably linked to God’s divinity, but she also had the joy of presenting him to the world. In this tapestry, the Holy Family is found in a fanciful scene engulfed in flowers. In addition to an angel that illuminates the scene, they are joined by three visitors from foreign lands. We see that although it was the Jewish people who were waiting in expectation of the Messiah, it was in fact the whole of humanity — including us — who are in need of his redemptive sacrifice. We often think about the sorrows of Mary’s life and all that she had to bear. But, there were also joys, especially in watching her son bring delight to so many whom he encountered. She certainly delights to have our gaze turned toward her son.

“The Flight into Egypt”

Giotto di Bondone, 1304-06, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

As life is defined by many unexpected moments, so, too, is Mary’s life marked by insecurity. Like all good parents, she and Joseph are willing to do what is necessary to protect their son. Because of the threats on his life, they were forced to take him to Egypt shortly after his birth. The journey could not have been easy for the newborn Christ or for Mary who had just given birth. We witness mother and child accompanied by Joseph and an angel, traveling by night away from their home. We are reminded of the sacrifices that parents make for their children whom they love. Mary wraps her mantle of protection over not only her son, but all of us who are also her children. We are reminded that God himself entered into a world of instability, and as a child he had the experience of depending on the strength and support of those around him. We also rely on the strength of others: our friends on earth and our friends in heaven, especially the guardian angel that God gives to each of us for our protection.

“Pietà”

Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1498-99, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome

One of the most famous, affecting and technically excellent sculptures in the world is that of Michelangelo’s “Pietà,” housed in the church that marks the burial place of St. Peter. The translucence of the marble has an almost lifelike quality as it forms delicate folds of fabric and the anatomical curves of skin and muscle. Mary holds the body of her dead son. The strength and bearing of her form contrasts that of the lifeless weight of Christ. Although she is crushed with anguish, she is still able to muster the composure to support her beloved son. She knows the pain of loss, but also possesses the strength to press onward. She is the image of one completely transformed by grace, who is able to accomplish superhuman tasks out of love for God. She is similarly able to support us in our pain, weakness and sorrow. She is the one to whom we can turn when our energies are spent and we need the support that only comes through God’s grace aided by Mary’s maternal intercession.

Virgin and Child mosaic

Artist unknown, 12th century, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

After examining scenes from the life of Mary, we turn our attention to images that focus our attention on aspects of Mary’s spirituality and personality. Within the ancient Basilica of Hagia Sophia we find numerous mosaics that still adorn the walls almost nine centuries after they were created. In this image, Mary holds the child Jesus who in turn holds a scroll in his one hand while the other hand is raised in an act of blessing. Both Mary and Jesus seem to look straight at us, the viewer. We are reminded of that eternal exchange of gazes: We gaze at God, and God gazes at us. Mary is presenting her son to us, who is at once powerfully self-possessed but also possessing that childlike openness. She is saying to us, in effect, “Look at my son: He is simultaneously welcoming you and also promising his protection.”

“Our Lady of Perpetual Help”

Artist unknown, 15th century, Church of St. Alphonsus, Rome

This image has offered comfort to countless souls throughout the centuries. Known as “Our Lady of Perpetual Help,” it hangs in the Church of St. Alphonsus in Rome. The icon is of Byzantine origin, and it depicts Mary holding the child Jesus as he envisions his future passion. The Archangels Michael and Gabriel hold the spear and the cross by which Our Lord will suffer. The frightened Jesus holds onto his mother’s thumb with both hands as he also begins to lose one of his sandals. Here we see the tenderness of a mother comforting her child. We believe that in his incarnation, Jesus experienced the fullness of the human experience, save for sin. As we gaze upon this icon of mother and son, it is easy to imagine ourselves in Jesus’ place, climbing into our mother’s arms seeking comfort amidst the storms of life.

“The Virgin Adoring the Host”

Dominique Ingres, 1852, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This image offers an unusual view of Mary. She stands before an altar, upon which sits a chalice and paten supporting an exposed host like a monstrance. Her hands are folded in prayer as she lovingly gazes at the Eucharist. Although the practice of adoring the exposed Blessed Sacrament is a later development within Catholic practice, we can imagine that Mary adored the Lord in various ways throughout his life. Certainly she must have gazed upon him as he slept in her arms when he was young. Perhaps she even retained a piece of clothing or a favorite toy of his that she would have held after his death and ascension. As she gazes upon the Lord sacramentally present in the Eucharist, she reminds us that we also experience the Lord’s tangible presence as we pray before the tabernacle or monstrance. The Lord is never far, especially having given us the gift of the Eucharist.

“Our Lady of Guadalupe”

God, Dec. 12, 1531, Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City

All of the previous images that we have contemplated have been works of human artists who utilized physical materials to create images that inspire devotion and contemplation. This image is utterly unique because, as best as we can tell, it is not the work of a human artist. Rather, it is God himself who is the artist. The story of its creation is well known. While walking among the hills of Mexico, Juan Diego encounters Mary, who invites him to gather the blossoms of roses that were unexpectedly blooming in winter. Gathering the flowers into his tilma (or poncho), he took them to show to the bishop of the diocese. Upon opening the tilma and allowing the flowers to fall, the image was left upon the fibers of his garment. Many of the elements of the image are familiar: Mary folds her hands in prayer. She stands upon the moon and is clothed with the sun as the woman described in the Book of Revelation. The miraculous image is a visible reminder of God’s work becoming incarnate in the world. The stars on Mary’s blue cloak match the stars of the night sky when St. Juan Diego encountered her. She appears with the facial features of a woman local to Juan Diego’s region. Even the miraculous image itself appears on a garment common among the local population. Although the image depicted is of Mary, the true object of focus, as it was throughout Mary’s life, is upon the Lord. We gaze in wonder at the work that God can do in the world through people animated by grace.

| ‘A PROFOUND SERVICE TO THE CHURCH’ |

|---|

|

In his new book “Beauty: What It Is and Why It Matters” (Sophia Institute Press, $14.95), John-Mark L. Miravalle writes a chapter entitled “Mary, the Tota Pulchra” (“all beautiful”). Of art depicting Mary and Jesus, he writes:”Historically, Mary and Jesus are the most popular subject matter in representational art. They have, moreover, taken on the forms of every culture and place. Every race has been represented by Christ; the clothing of every culture has been worn by Mary.”So, what’s the takeaway for Catholic morality? Morality is nothing other than discerning and following the proper way of fulfilling the human person. Morality is simply how people become the people they were made to be. Depicting Christ and Mary under every admirable aspect, presenting them with every honor that any culture can bestow — this is a way of showing humanity how to be fully human. Such art shows us how to live.

“Art dedicated to Our Lord and Our Lady isn’t simply an exercise in taste or in refined religious sensibility; it can make us delight in being human again and give us the impetus to strive for our own happiness. Anything that helps us appreciate the beauty of Christ and his mother is a profound service to the Church and the world. That kind of work can save people.” |