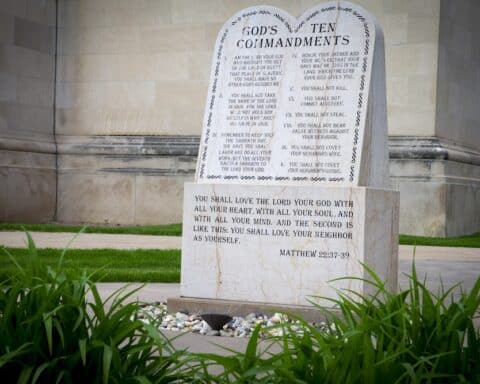

This is the third installment of a 10-part series looking at the Ten Commandments.

The commandments are personal. All of them are founded upon one inerasable fact: God speaks to us. Our first duty, therefore, is to hear. What we are to hear above all is that the Lord is our God, the Lord alone. The First Commandment makes that explicit.

But when we hear the Lord announce himself as our “God,” what do we really hear? It might seem like “God” is a job title or function, but what God speaks to us is far more personal. God gives his name. And that name is the focus of the Second Commandment: “You shall not invoke the name of the Lord, your God, in vain.”

How God gives his name

As we read in the Book of Exodus, when God beckons Moses at the appearance of the burning bush and commissions him to deliver the Israelites from slavery, Moses asks to know the Lord’s name. The name that God gives is what we have grown accustomed to translating as “I AM.” This is, of course, a mysterious name since it is as much a statement of absolute presence as it is a personal name.

But there is more mystery to this name than we typically assume. While “I AM” is a good and faithful translation, the name that God gives carries, in Hebrew, another and equally important sense to it. The other way to translate that same name into English would be “I will be what I will be.”

By this second sense, when the Lord gives his name he is telling Moses to tell the people: “If you want to know who I am, watch what I do because what I do will tell you who I am.” The upshot for the Israelites is that there is no way for them to be able to know the name of the Lord without paying attention to the Lord’s deeds.

Who does God then reveal himself to be? Actually, we can listen to the Israelites themselves tell it when they stand on the other side of the Red Sea. They have been delivered from their captors and freed from slavery. And then they sing: “I will sing to the Lord, for he is gloriously triumphant; horse and chariot he has cast into the sea. My strength and my refuge is the Lord, and he has become my savior. This is my God, I praise him; the God of my father, I extol him” (Ex 15:1-2).

Who is the Lord God? What is his name? Right here, the Israelites proclaim that they know because they have seen his works, they have known his deeds, and they have reaped the benefits. Each of them sings that the Lord is my strength, my song and my salvation. That is God’s name.

God’s name is delivered through God’s deeds, and that name is pronounced when the Israelites sing to their God in gratitude.

The Name of Jesus

The deeds and proclamations in the Book of Exodus do not contain all there is to say about the name of God; the name of God is given in full in the person of Jesus. Pope Benedict XVI muses on this in his short book, “The God of Jesus Christ” (Ignatius Press, $15.95):

“His own name, Jesus, brings the mysterious name at the burning bush to its fulfillment; now we can see that God had not said all that he had to say but had interrupted his discourse for a time. This is because the name ‘Jesus’ in its Hebrew form includes the word ‘Yahweh’ and adds a further element to it: God ‘saves.’

“‘I am who I am’ — thanks to Jesus, this now means: ‘I am the one who saves you.’ His being is salvation.”

The action and deeds of God for his people are not complete in Exodus; they are complete in Jesus. As we read in the Gospel of John, he who was on high with God and who was God on high, came down: “And the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (Jn 1:14).

As Benedict also notices, there is something delightful in the literal name of “Jesus.” His name literally means “God saves.” This means that in both the spiritual and the literal sense, “Jesus” is “God’s saving action.” He is the name of God; he gives God’s name to us.

But if Jesus is the fullness of God’s name — “the name that is above every other name,” as Paul writes to the Philippians — then what was true of the Israelites on the other side of the Red Sea is also true of Christians if we are to call the name “Jesus.” The Israelites knew God’s name because they recognized him as their salvation, their savior. He was the one whom each of the Israelites called my strength, my song, my salvation. For Christians to know God’s name in full, we must recognize Jesus as our salvation. And that means seeing his deeds, accepting his deeds, and being grateful.

The only way to pronounce the name of God is to praise what Jesus has done for us. We must proclaim our own gratitude.

Revering the name of God

The Second Commandment is a commandment about gratitude, and it is also a protection against ingratitude. Taking the Lord’s name in vain means being ungrateful. It means taking for granted what the Lord does.

Could you imagine the Israelites on the other side of the Red Sea doing anything other than rejoicing at the name of God and shouting their thanks and praise? We might think that would hurt God’s feelings, but that is the wrong way of thinking about it. We should instead think about how harmful ingratitude would be for the Israelites in Exodus. For them to revere the name of God means to recognize what God has done for them. To take that name in vain would mean forgetting that they have been liberated and that God is the one who liberated them. In other words, to become ungrateful would be to forget the basis of their own freedom, to forget what makes them who they are, and to forget their own identity as the people whom the Lord has looked upon and saved.

When someone today, “takes the Lord’s name in vain,” whether in a moment of frustration or displeasure or even surprise, we do not usually think that that person is giving all the basis of their freedom, their identity and all that. But maybe we should think a bit more about how precious that name is, or about how much really rests on the Lord’s action in our lives. To be more mindful about how and when that name is used can become, for us, a little sacrifice or a small regular exercise that forms us in becoming more grateful. Taking care with the name of the Lord and not speaking it in an ungrateful manner is the flip side of learning how to live in gratitude for the life of Christ, given for us.

But revering the name of the Lord is not just about what we refrain from doing; it is at least as much about what we practice doing. One of the most regular practices for Catholics is itself an opportunity to practice reverencing the Lord’s name: making the Sign of the Cross.

When we mark ourselves with the Sign of the Cross, especially when we dip our fingers in holy water as at the entrance to a church, we reclaim our identity as one who lives within the love and life of God. Notice what we say: “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

Name. It’s singular. We do not say “in the names of,” as if there were three separate reference points somewhere out there. No, we acknowledge the one God in three persons. We offer ourselves into the communion of this one name, of this one life, of this one God in whom we live, and move and have our being.

So, what can we do? We can slow down and breathe deeply when we make the Sign of the Cross. To do it quickly, almost perfunctorily, is a tiny sign of irreverence, of ingratitude, of taking it for granted, of vanity. To be given that life in that name is a gift.

This is a way of renewal in obedience to the second commandment.

Leonard J. DeLorenzo, Ph.D., works in the McGrath Institute for Church Life and teaches theology at the University of Notre Dame. His new book is “A God Who Questions” (OSV, $12.95).