Looking for another book by a different author, I’d run across Barfield on the mantelpiece in our bedroom; a few days later, cataloging some volumes in our library, I realized that “Hannah Coulter” was the only one of Berry’s novels I had never read, and the next day was pleasantly surprised to hear Doug Tooke recommend it on his “Renovo” podcast; a day or two later, having finished rereading Percy’s “Love in the Ruins,” I noticed that Apple Books was selling a combined edition of Percy’s “The Message in the Bottle” and “Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book” for the impulse-buy price of $3.99. I impulse-bought it and, on impulse, started reading it.

Barfield, as a philosopher, can be tough going, but “Saving the Appearances” was, for me, one of those books that forever change how you view the world and the nature of man. Percy’s “Message in the Bottle” is, at heart, about the nature of those life-changing experiences. And “Hannah Coulter”? Berry’s 2004 novel may be his crowning achievement, a meditation from the inside out of a life lived, not as an “individual,” but as a person in relation to others, with all that implies, including the way in which such a life participates in the inner life of God.

Wendell Berry is not Catholic, nor are any of the characters in “Hannah Coulter,” but Doug Tooke was right not only to include the novel in his “Renovo” episode on Catholic fiction, but to list it first. If all truth belongs to God, all fiction, to the extent that it is true to the deepest, most universal experiences of life, is catholic, at least with a small “c.”

And sometimes with a capital “C.” Take just three lines from “Hannah Coulter,” from a meditation by Hannah on what memory means when we realize that we cannot truly live in the past or the future but only in the present (“now and now and now”): “When you remember the past, you are not remembering it as it was. You are remembering it as it is. It is a vision or a dream, present with you in the present, alive with you in the only time you are alive.”

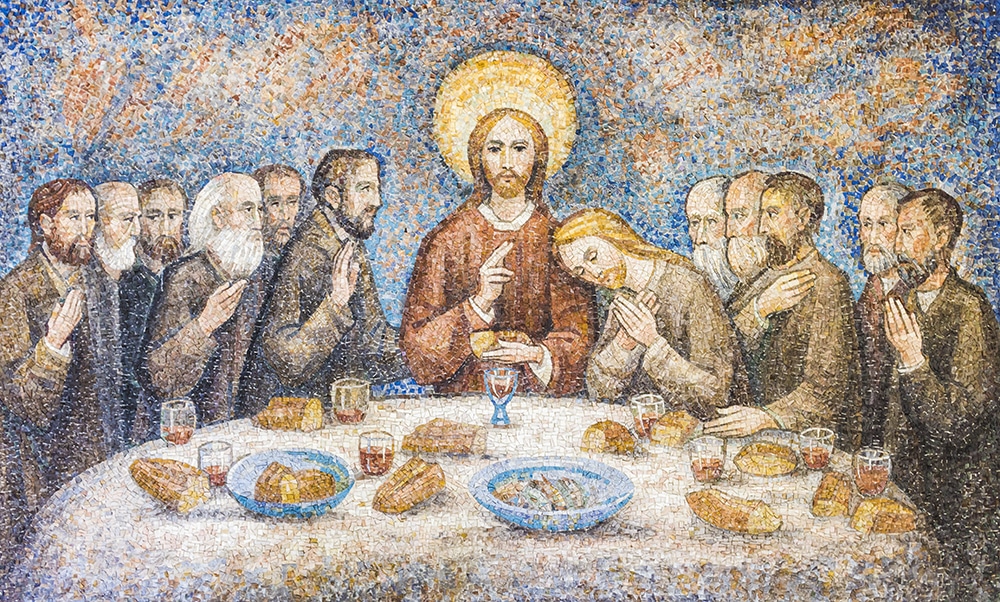

To paraphrase Hannah, when we remember that sacrifice, we are not remembering it as it was. We are remembering it as it is. Christ’s sacrifice, both on the cross and at the Last Supper, is present with us in the present, alive with us in the only time we are alive.

That’s what it means to participate in the Eucharist. That’s what it means to participate in the life of God himself.

That’s what it means to remember.

Scott P. Richert is publisher for OSV.