When Father Yaroslav Koval was a boy, his mother and grandmother took him to hidden rooms and catacombs where priests celebrated the Divine Liturgy in secret. They prayed in silence to avoid detection by the Soviet’s communist regime that was persecuting the Ukrainian Catholic Church. If discovered, they could be imprisoned.

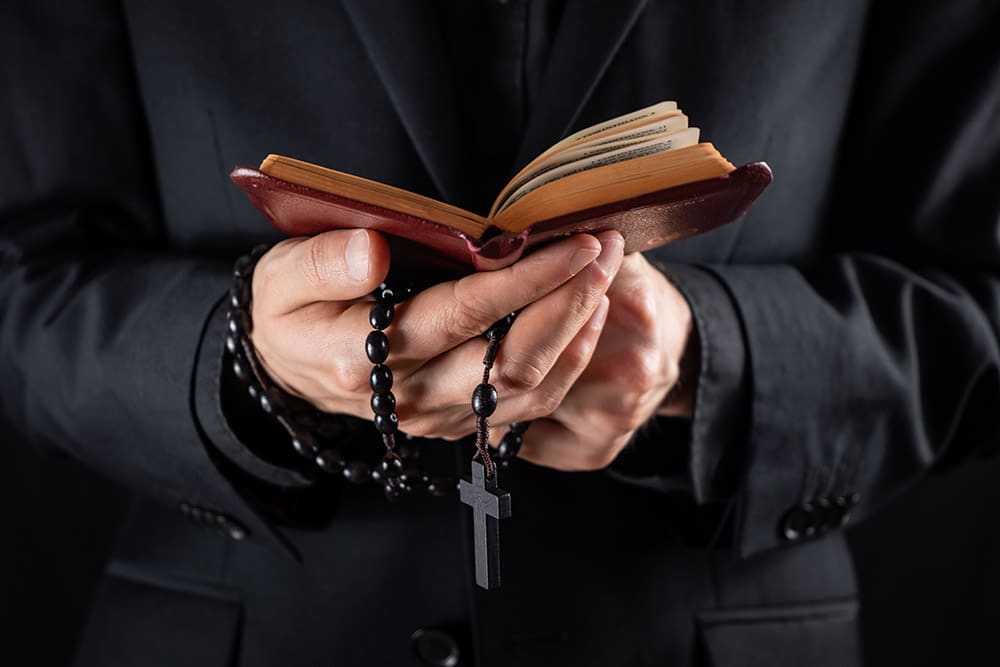

His grandmother prayed the Rosary every day in a small room, too, and he credits her prayers and the faith of his late parents and grandparents with his journey to the priesthood.

“Our prayers are like oxygen to us,” he said. “Without oxygen, we cannot live. Without prayer, we cannot have a spiritual life.”

Read more vocation articles here.

Father Koval came from Ukraine to Pennsylvania in 2010. He is administrator of three Ukrainian Catholic churches in the Eparchy of St. Josaphat — St. John the Baptist in Pittsburgh, Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in New Alexandria, and St. Vladimir in Arnold where he lives with his wife, Oksana, and daughter, Veronica.

In addition to his morning, afternoon and evening prayers, he prays in the Eastern tradition on a knotted rope called the chotki: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the Living God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Praying, he said, is part of a Christian’s journey to climb a mountain in the direction of heaven.

“With every prayer, my voice goes to heaven,” he said. “I thank God for everything I have. I ask God for grace and for blessings for others and to help others. These prayers are reminders that I have to walk in the presence of God.”

Unified in prayer

The Sisters of Mary Morning Star in Monona, Wisconsin, pray daily with two holy hours, Eucharistic adoration, five Liturgies of the Hours, Mass, a half hour of thanksgiving and silent adoration after Mass.

“My faith is strengthened by the prayer intentions in seeing how much people believe in the power of our contemplative life and intercessory prayer,” said Sister Mary Thomas Leary, one of nine sisters at that location. “It inspires me to bring those prayers to the Lord, like Mary did at Cana. She didn’t tell Jesus how to solve the problem of no more wine. She just presented the problem to him, trusting that he would know the best response.”

Intercessory prayer reminds her of the universality of the Church, of being united in the Body of Christ. The requests for such grave needs, she said, “become our own sufferings,” making it all the more important to turn them over to Our Lady.

Bringing people to prayer

Father Daniel Ulishney is pastor of St. Mary’s in Export and St. John Baptist de LaSalle in Delmont in the Diocese of Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

“A diocesan priest has to be an ambassador for many styles of prayer,” he said. “I ask people, ‘How do you pray well?’ The Lord speaks to each of us so that we can become more familiar with his voice and better cultivate our own spiritual lives.”

His own prayer life was influenced by the charismatic renewal in his youth, and he loves the liturgy, finds comfort in Eucharistic adoration and has a devotion to Mary. He calls prayer the engine that powers his life and enriches his commitment to connect people to God through intercession. That’s a source of personal strength and inspiration to him.

“A parish priest shares in people’s joys and sorrows, and you bring that to prayer,” he said. “I think about the people on my prayer list and the circumstances they’re carrying. When I’m praying for them, I become more authentically myself as a priest. It’s also important for the faithful to intercede in prayer for their priests and entrust them to Our Lady.”

Homily preparation

Deacon Gene Fadness, a convert in 1999, was ordained into the permanent diaconate for the Diocese of Boise, Idaho, in 2015 and is assigned to St. Mary Parish in Boise.

His evangelical background in Bible study enriches his prayer life.

“Studying the Bible,” he said, “is a form of prayer, and you’re led by the Holy Spirit to study something that’s impressed on your mind.”

That leads him to cross references or documents from Church fathers when he’s praying the Liturgy of the Hours.

“There will be a passage that leaps out to me that not only helps in my spiritual development, but also helps me to prepare my homilies,” he said.

Sometimes people tell him that his homily spoke to them and was an answer to their prayers.

“I look at that as a fruit of prayer,” he said. “I know that prayer works.”

Deacon Fadness, the editor of the Idaho Catholic Register, is married and has three children and eight grandchildren. His wife Sharon, a cradle Catholic, influenced his journey to conversion and to a daily prayer life even before he entered formation. He also has a devotion to the Rosary.

“I have a list of people I’m praying for every morning and night,” he said. “A lot of parents and grandparents are asking me to pray for their children to return to the Faith.”

Prayer and work

The 20 to 30 prayer requests received every day at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in Abiquiu, New Mexico, are placed in a reed basket by the altar. The Benedictine monks are invited to take them and to hold those people in their prayers.

“Our mission is to pray for the world,” said Brother Chrysostom Christie-Searles, the monastery guest master. “This is what our life is about. It’s not that we just sit and pray. Everything we do is prayerful — our work, our interaction with guests and how we relate to the community. We pray our [Divine] Office seven times a day, as well as Mass. In short, prayer is jet fuel for our jet airplane.”

The life of a Benedictine is anchored in ora et labora, which is prayer and work. There are opportunities for a prayer life of solitude and for coming together in community.

“That’s what makes monastery life special, that we are engaging in prayer life as a community as we pray for the larger community and as we pray for the world,” Brother Chrysostom said. “There’s a humility in praying for others, and it’s actually reaffirming to the person who’s praying — in this case, the monks — that we, too, need prayers. People look surprised when we ask them to pray for us, but we need prayers, too. Please pray for us.”

Maryann Gogniat Eidemiller writes from Pennsylvania.