One of the most remarkable facets of Catholic tradition is the treatment of relics. These are, ordinarily, the mortal remains of a saint. But the objects kept and reverenced as a memorial of a holy person are also known as relics. The word comes from the Latin term relinquo, meaning “to leave behind.” Outlined here are first- and second-class relics, respectively. There are also such things as third-class relics, which are items touched to a first-class relic.

Rich is the tradition of relics, and historic is the practice of venerating, but modern people are still troubled by the idea of authenticity. How do you know for sure that sliver of bone is really from St. John Vianney? Even harder to imagine being genuine are relics from early Christians, such as those of the apostles. When a person digs into the history of relics, we find them changing hands several times, being lost for long periods of time, and worst of all, multiple claims. There are two heads of John the Baptist. But of course, the forerunner prophet of Christ was not polycephalous. Someone has lied, and one of the heads claiming to be his is most obviously not.

When the word “authentic” is used in reference to a relic, it means that the relic comes from credible sources. And in some cases, diligent efforts have been taken to ensure that the relics are from the correct body and identify the correct body part. But there is a caveat: this understanding is not with strict certainty, but prudent, human confidence. In other words, we have it on good authority.

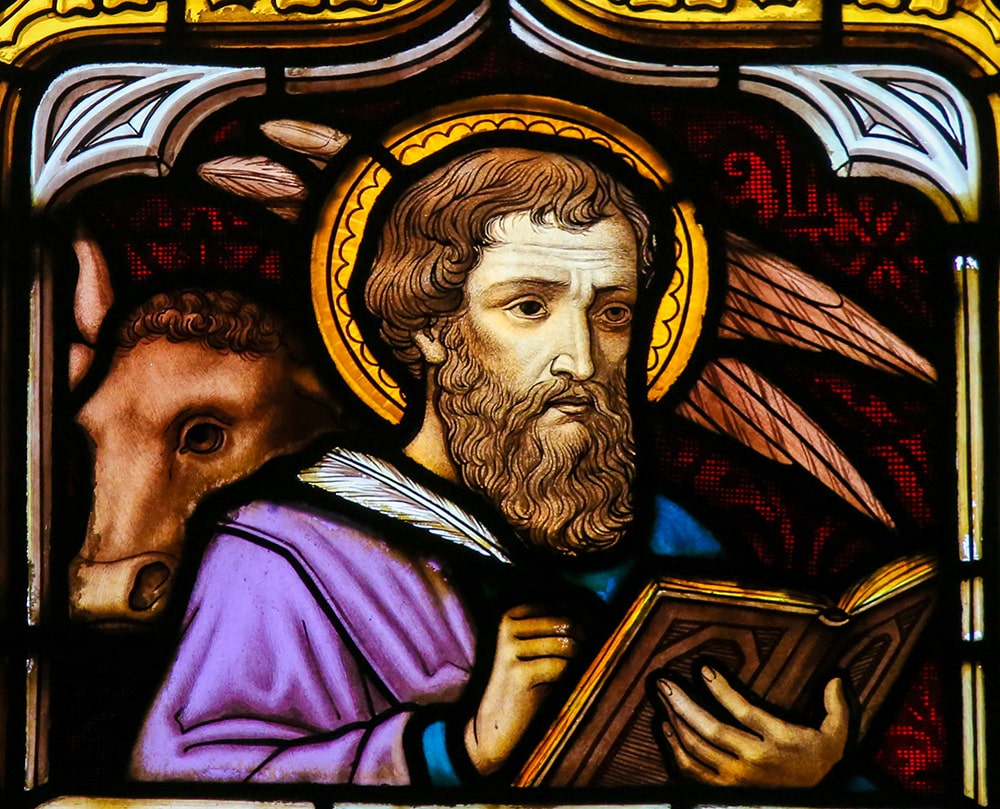

Notwithstanding that level of certainty, we still strive to apply modern technologies to determine if a relic is indeed genuine. To this cause, painstaking efforts have been taken to verify authenticity using noninvasive technology. Take, for example, the treatment of the bones of St. Luke the Evangelist, whose feast is celebrated by the Church on Oct. 18.

A scientific discovery

It is well known that St. Anthony, the famed patron of lost things, is buried in the Basilica Abbazia de Santa Guistina in his native Padua, Italy. But in the same church rests the body (though not the head) of St. Luke, who wrote the third Gospel. There is a skull in Prague that is said to be from St. Luke, who tradition holds was hung from an olive tree in Thebes, Greece. This separation of body and head certainly makes people wonder about the authenticity of his relics.

In the 1960s, approval was given to partly redesign the side chapel and altar at the Padua basilica where Luke’s remains are said to have been located since A.D. 1117. This process would take more than 30 years to complete. In the middle of the process, the Orthodox Archbishop of Thebes requested that a significant fragment of the remains of St. Luke be returned and placed in a tomb located in his original resting place. Taking advantage of the need to comply with canon law on the separation of relics, the bishop of Padua set the wheels in motion to verify the authenticity of the bones. The investigation prompted St. Luke’s tomb to be opened for the first time since 1562.

When the tomb was opened, researchers found the remains of a body containing no skull, just teeth buried with the rest of the bones. The skull in Prague claimed to be that of the evangelist was requested and promptly sent to Padua to be studied. After a long investigation of the history of the body, the report was finalized in 2001. The bones belonged to a man roughly 85 years old, 5 feet, 3 inches tall, and neck trauma that indicated he was hung to death. The skull from Prague matched the neck vertebrae and had features like that of Antiochians from the first century. The teeth from the tomb in Padua were also a perfect match.

The case of St. Luke’s relics is a fascinating one. Not only is the history filled with intrigue — Venetian crusaders are said to have stolen the relics, yet, relics of the crusades commonly ended up in France rather than the Veneto region of northern Italy — it is also one that questions our collective faith in relics. Do we believe in the authenticity of relics only when they are confirmed to our chosen standard? And perhaps further, do we assent to the power of relics only if we are satisfied with proof?

With modern analysis techniques available, the Church will permit and assist in these types of noninvasive investigations. The question remains: Do we need them? The fact is, there is no scientific procedure that will prove without a doubt that an ancient relic is authentic. It will always come down to faith and judgment. When it comes to the genuineness of relics, no matter the class, we should be mindful of the reliability of tradition, but also we should be aware that we are dealing with human discernment, not divine revelation.

Who (and how) we worship

As to an assent in faith to the power of relics, there are some points to consider. First, we are not required as a matter of faith and obedience to venerate relics. Furthermore, the Church does not force any believer to acknowledge the authenticity of any relic. That is because, as a secondary point, relics belong more directly to piety. The Catechism of the Catholic Church encourages the veneration of relics by all Catholics: “The religious sense of the Christian people has always found expression in various forms of piety surrounding the Church’s sacramental life, such as the veneration of relics …” (No. 1674).

Recognizing this, relics do indirectly correspond to faith in Christ. Catholics call the worship that is due God alone latria; veneration is known as dulia. St. Thomas Aquinas notes in his Summa Theologiae that that the respect given to the saints is a duliae relativae, or a veneration relative to the worship of Christ, since the respect paid to the saints continually orients us to the Savior. Lumen Gentium puts it this way: “For every genuine testimony of love shown by us to those in heaven, by its very nature tends toward and terminates in Christ who is the ‘crown of all saints,’ and through him, in God who is wonderful in his saints and is magnified in them” (No. 50).

Relics, then, are relevant of — and related to — the Incarnation, where all humans are animated in a combination of the body and spirit. The importance of this is seen in the sacraments: elements of the physical affecting the reality of the spiritual. It is this powerful belief that fights the gnostic worldview — still rampant in modern culture — that there is a sharp divide between the material and the spiritual. Christianity is not a dualistic religion. Our faith is based on the sanctification and salvation of the whole person — body and soul.

It is fitting then, that Catholics honor the bodies of the members of the Body of Christ: “As a body is one though it has many parts, and all the parts of the body, though many, are one body, so also Christ” (1 Cor 12:12).

The saints have a right to be venerated, and it doesn’t diminish the worship we owe to God. Perhaps our renewed confidence in relics like that of St. Luke will draw us nearer to him.

Shaun McAfee writes from Louisiana.