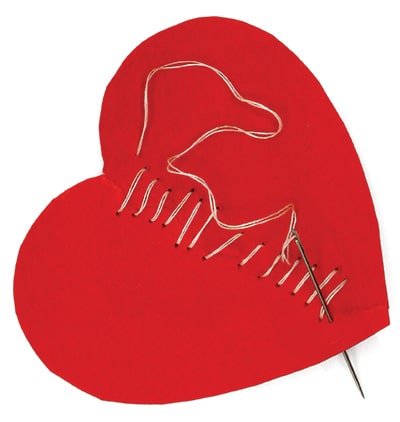

“Rend your hearts, not your garments,” the prophet Joel commands. Listening to these words during Ash Wednesday Mass, I wondered what this prophetic call to repentance could mean for hearts already rent or wounded — hearts exhausted from a difficult, Lenten year.

“‘What am I hoping to be healed from in Lent?’ That’s a good thing to stop and ask myself,” said Ryan McQuade, 28, a graphic designer in Arizona. This Lent, he is bringing the wounds of self-hatred to Christ for healing.

“I’ve despised parts of myself, and have been taught to despise parts of myself,” he said.

McQuade attended Franciscan University of Steubenville, majoring in theology and catechetics. Throughout his life, he imbibed a particular vision of masculinity that never quite fit him.

Growing up, McQuade said, he was taught that the ideal Christian man was straight, married with kids, eloquent, confident in all his answers and free from temptation.

“I think that was just very difficult,” said McQuade, “because here I was: not straight, not married, not with kids, doubting a lot, struggling a lot.”

After trying to conform to this image for the better part of a decade, McQuade said he came to realize that this image of idealized masculinity he thought he had to conform to was an illusion.

In “New Seeds of Contemplation,” Thomas Merton wrote: “Every one of us is shadowed by an illusory person: a false self. This is the man that I want myself to be but who cannot exist, because God does not know anything about him.”

As McQuade described, our false selves are always tinged with hatred for our true selves. That false self is an idol, made in the image and likeness of the world’s ideas of success or strength or beauty. Repentance means stripping ourselves of the false selves, and, instead finding that true self, made in God’s image and likeness.

McQuade’s journey of healing has led him to a fresh realization of God’s love as patient and kind.

“God is no longer the person I’m going to in order to actively try to change everything about myself,” said McQuade.

Naming our vulnerabilities

In the Gospels, when God shows up, there are two key themes. Christ asks for truth and brings healing.

Christ asks his speaker to tell them the truth, no matter how unacceptable or uncomfortable it is: Who is your husband? What do you want me to do for you? Who do you say that I am? And Christ answers this truth with healing.

Encounters with Christ in the Gospel do not end with healing — they begin with one. Before Jesus even says to us, “Come and follow me,” he begins with healing us. Christ constantly demonstrates who he wants to be for us by healing us.

Healing begins with naming our vulnerabilities, naming our weaknesses. God, as McQuade discovered, is the one who accepts these vulnerabilities with gentle love. The hearts we are called to rend are our own, not some better version of ourselves.

Accepting God’s love for us is the only way to be a sacrament of God’s love to others. The works of mercy — feeding the poor, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless — are the fruit of a heart that has encountered God’s mercy herself.

Personal and communal healing

Nate Tinner-Williams sees a direct link between personal healing and communal healing.

Tinner-Williams, 29, is the co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger and an aspirant with the Josephite priests in New Orleans.

“The Black community needs healing right now,” said Tinner-Williams. “And I, as a Black man, am in need of healing.”

The killings of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery this past year were wounds that brought home the way in which American culture devalues Black people. In response to the wounds of this past year, Tinner-Williams said that he has found healing by giving a voice to his community.

Tinner-Williams answered his call as a healer by founding Black Catholic Messenger. He saw a dearth of Black voices in American Catholic media, and a need for more Black Catholic publications. He described Black Catholic Messenger as a place for Black Catholics to tell their own stories from their perspective. He hopes it will be a “venue of healing and a venue of light.”

Healing means to make something whole, to stitch back together something wounded, torn. Tinner-Williams’ work strives not only to heal the Black Catholic community, but to heal the larger Catholic Church in America. He hopes that the American Catholic Church will embrace Black American Catholicism as an essential thread in the heritage of their Catholic faith, as part of each Catholic’s story.

Being made whole

Healing means being made whole. It means being reunited with the parts of ourselves, our Church or our community that have become sundered from us.

A week before Ash Wednesday, a friend’s text reminded me that Lent was on its way. I didn’t feel ready. I felt exhausted and weak and not strong enough for Lent.

But asceticism is made for tired people like me. The process of training our desires to seek God is not necessarily an exercise of strength. Reshaping of our hearts through repentance, the journey of conforming to Christ, always begins with our own healing. And healing begins with acknowledging your weakness. You can’t strengthen muscles if they have torn. In order to build up their strength, you first have to begin by healing the wound itself.

During my junior year of college, I was groomed by an abusive priest. After a sordid and painful nine months, I finally extricated myself from the relationship. The intense pain and confusion that marked that year extended through many, many years after.

Process of rebuilding

Healing is a slow process. Abuse seeps its way into every layer of life; so, healing, in the same way, requires an equally thorough process of rebuilding.

First, every day is spring cleaning. Seasons of life are spent intensely scrubbing, attempting to eradicate the rot that infiltrated every interior corner of the heart and soul. Healing, like conversion, is a constant journey. There’s a reason that we repeat Lent year after year.

When my friend texted me, I thought, like many Catholics on the eve of Lent, what do I need to work on? What do I need to “get better at”? But it occurred to me that perhaps I was asking the wrong questions.

Sometimes old wounds sting more than usual. Pain, doctors tell us, is a sign from the body to the brain that it needs help. So, too, pain in our hearts is a call for care and attention. Feeling this decade-old hurt still festering, I decided perhaps this Lent, before I rend my heart, it is time to take my heart to God to repair the tear.

Lenten road map

The Lenten practices of prayer, fasting and almsgiving provide a road map — three practices through which my heart can encounter God. And, along with Nate Tinner-Williams, I believe this deeper encounter of Christ the Healer will bear fruit in healing for my community. Resurrection is the mark of a community — and our own healing allows us to become signs of resurrection to the resurrected body of believers.

During Lent, we commit to the process of conversion — we enter the desert of our woundedness with Christ, who can re-create our wounds into the shape of resurrected love. The ultimate goal of Lent is not spiritual power or perfection, but to retrain our hearts so resurrected love and not our wounds, are the ground of who and what we are.

This Lent, may we all journey deeper into the love that made us, who yearns to heal us — who really does come to save us, to make us holy — that is whole.

Renée Darline Roden writes from New York.